1865 and all that

As Nottingham Forest’s anniversary year draws to a close, Alex Walker takes a wider look at the momentous year that was 1865…

While 2015 will not be remembered as an auspicious year in Forest’s history, club records have at least been broken in the publishing industry. Amongst the bumper crop of Garibaldi-tinted titles to hit the shelves in time for Christmas this year, Forest Forever by Don Wright and an updated edition of Philip Soar’s Official History both cover the whole span of the club’s existence, while others books have focussed on particular eras such as the 1960s and late ’70s.

Few of these books, however, spare many pages for the event the 150th anniversary is supposed commemorate, namely the foundation of the club. This isn’t a failure or neglect on the part of the authors – lack of reliable evidence means there simply isn’t much to say about the events of 1865 that were to have such an impact on the lives of everyone reading this article.

However, just as a scientist knows that negative results are just as valuable as positive ones, the historian – or budding history buff in my case – must remember that lack of evidence is itself evidence. The 1860s were a fascinating period in British history and though we may not even be certain what the score was in the Reds’ first match, we can infer a lot about the circumstances of it from the various other things that were happening at the time.

Club culture

The scarcity of contemporary reports and records mean histories of Forest’s early years tend to be patchworks of vague newspaper notices, surviving account books and administrative minutes, combined with educated guesswork. The lack of first-hand documentation alone tells us that Forest were not, during these formative years, much rated amongst the emerging footballing community. The leading clubs of this dawning age were the subject of vivid memoirs and gloriously verbose Victorian press reports, but Forest were largely ignored outside Nottingham for 30 years or so.

This was mainly because London and Yorkshire were the real hotbeds of association football, followed by significant developments in Glasgow (where Queen’s Park pioneered a new passing style) and the North-West of England (the birth place of the professional footballer). In Forest Forever, Don Wright declares that Sheffield FC – founded 1857 – were the “world’s first football club”. Juxtaposed with descriptions of the successive births of Notts County (1862) and Forest, this simplistic view gives the impression that Sheffield FC spent five years waiting around for someone to play, when in reality there were already dozens, if not hundreds of other teams already playing the game in some form or other.

Though it’s tempting to refer to familiar names like Sheffield, Notts and Forest when describing the earliest clubs, it is also extremely misleading. There are reports of organised games in the Sheffield area as early as 1843. Organised is a key word here – these were the first known matches contested between small teams from rival towns, played in front of a crowd and sponsored by local pubs, rather than mass brawls like the Shrove Tuesday games associated with various towns, particularly Derby (and some might say the standard there has improved little since), going back to the 12th century.

By the 1840s, mob football was being violently quashed by the authorities who worried that it was a pretence for anarchy, but games that involved a ball as a loose excuse for a scrap were simultaneously gaining popularity in English public schools. Here, rather than foretelling the downfall of civilised society, they were seen as an ideal method of teaching boys to tough it out in a muddy field while maintaining a modicum of discipline, the qualities the nation would later rely on from these chaps in foreign battlefields.

Though they resembled mini wars, many of the boys nevertheless enjoyed the various rough-and-tumble games identified as foot-ball that were played at Eton, Harrow, Rugby, et al. At university, these young gentlemen organised themselves into old boys’ clubs to continue the pursuit, but the disparate rules practised at each school meant games between the clubs were farcical, so different codes developed independently.

Nevertheless, reunion matches between public school alumni became a regular occurrence in civilian life, for the upper classes at least. While football was gaining a foothold in Sheffield, it was simultaneously laying solid foundations in London. The upshot of this was that by 1865, not only were Nottingham Forest the latest of dozens of clubs to be started, they weren’t even the first one called ‘Forest’.

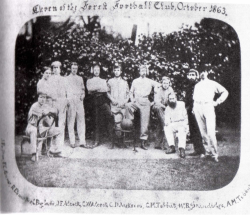

That honour goes to the club founded by John and Charles Alcock, educated sons of a wealthy shipbroker from Sunderland. In 1859 they created the Forest Football Club (pictured), named after Epping Forest, the location for games between former Harrow pupils. In 1864 this club became Wanderers FC, best known for beating Royal Engineers in the first FA Cup Final in 1872.

That honour goes to the club founded by John and Charles Alcock, educated sons of a wealthy shipbroker from Sunderland. In 1859 they created the Forest Football Club (pictured), named after Epping Forest, the location for games between former Harrow pupils. In 1864 this club became Wanderers FC, best known for beating Royal Engineers in the first FA Cup Final in 1872.

As early as 1863 there were enough clubs in London – strictly amateur and strictly made up of the educated classes – for an official set of rules to be necessary, so the Football Association was established at – as these things invariably were – a London tavern.

Sheffield FC weren’t invited to contribute any regulations from their own rulebook until 1867, though many of the ‘Sheffield Rules’ were eventually incorporated into the sport. This, rather than the FA’s code, would have been the set of rules Forest, County and other northern teams played to, more recognisable as our modern game, though still allowing catching and charging. Most controversial were the rules about free-kicks and penalties – the gentlemen of London resented the implication that a foul might be seen as having been committed deliberately!

Different class

Nottingham was probably the second northern city to adopt modern football to a notable extent, but the West Midlands and Lancashire soon overtook the East Midlands in terms of pioneering the game, most significantly in hiring working men to play as professionals. The first paid players were employed surreptitiously by local factory owners and drafted into teams as ringers, but professionalism was eventually sanctioned in 1885.

Until the advent of professional players and the all-conquering (and all working class) Preston team of the 1880s, football was a game for the upper classes. Working people’s rights to gather for any purpose, as well as their right to common land on which to gather, were subject to erosion over several centuries – as far back as Cromwell, the commoners’ football games had been suspected of being covers for sedition. The football crowds of the 1860s were well-dressed and well-behaved, even though the gentlemanly game was anything but gentle – the working lads, on the other hand, could ill afford to get injured and miss work as a result, hence the rules that discouraged ‘hacking’.

It goes without saying that in the 1860s, working people – particularly those in towns and cities – simply didn’t have the time for sporting pursuits their wealthier counterparts enjoyed. The factories and mills of the Industrial Revolution needed to be running to full capacity to maintain their profits, which meant workers were required during daylight hours on all days when religious tradition wouldn’t prohibit it. It wasn’t until the mid-1870s that trade union pressure turned Saturday into a half-day, a watershed moment for British sport and culture in general.

As an aside, there is some suggestion that the five-day working week most of us now enjoy (if that’s the right word) was adopted in the early 20th century to allow Jewish workers to observe the Shabbat, which is a nice counter-argument to any UKIP anti-immigration stance, although it seems the real reasons were somewhat more cynical. In 1926, Henry Ford gave all his factory employees the whole of Saturday off, not out of generosity or concern for their health, but so they would have more spare time to be consumers – perhaps even customers of the Ford Motor Company. The trend spread across the world at the same pace as American consumerism itself.

Here we should note that 1865 was a significant year for American capitalism, with the New York Stock Exchange opening its permanent headquarters on Wall Street, the American Civil War ending in victory for the more progressive North, and of course the abolition of slavery with the 13th Amendment. In April of that year, President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated at Ford’s Theatre in Washington DC.

Though it would take several decades for the repercussions of these events to have an effect on the lives of British working people, it is worth pausing to reflect that it was from America that the idea of ordinary people having leisure time originates. Slavery was abolished in the United Kingdom in 1833 (and the rest of the empire 11 years later), but even in 1865 the lower classes were effectively slaves to poverty thanks to various land reforms that not only swallowed up green spaces but also put rent demands in the hands of private landlords (who often owned the local factories and mills too).

Change was in the air though. Novelists like Charles Dickens and Anthony Trollope satirised the decadence and lamented the squalor of the age. Darwin’s On the Origin of Species had been published in 1859 and was already gaining sway in the scientific community (and upsetting the religious one). Europe as a whole was still reeling from the various political revolutions that occurred in 1848, the same year Karl Marx published his Communist Manifesto.

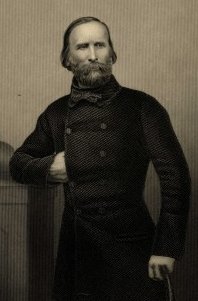

Perhaps most significantly to our story, the Italian revolutionary general Giuseppe Garibaldi (pictured) – leader of the rag-tag army of ‘red shirts’ who helped unify Italy in a popular uprising – had visited London in 1864 and was “universally popular in England”, as Philip Soar notes.

Perhaps most significantly to our story, the Italian revolutionary general Giuseppe Garibaldi (pictured) – leader of the rag-tag army of ‘red shirts’ who helped unify Italy in a popular uprising – had visited London in 1864 and was “universally popular in England”, as Philip Soar notes.

That Forest’s founders were admirers of Garibaldi suggests they were more forward-thinking than many of their contemporaries, but we should not kid ourselves that club members were anything but middle class or that the shilling-a-week club subscription was anything but exclusive.

Many of the northerners who founded football clubs in the 1860s were the nouveau riche of the Industrial Revolution – or rather the children of the nouveau riche, given the benefit of public school education alongside their social betters. On the playing fields these boys found their equality and when the necessity of taking over the family businesses brought them back to the provinces, they gathered the local men around them to continue their sport, much as lords of the manor would bolster their cricket XIs with the downstairs staff.

What we know about Forest’s founding members, such as shopkeeper Charles Daft or Nottingham High School-educated lace merchant W. H. Revis, suggests these men were not quite of the same stock as the Alcock brothers or the factory owners who founded Blackburn’s two football powerhouses of the 1870s, Rovers and Olympic (not forgetting nearby Darwen FC, created by an ex-Harrow mill heir). However, they were dynamic and affluent figures if the donations Revis made to Nottingham University in later life and other business legacies of the Forest founding fathers are anything to go by.

Forest club members were also unlikely to have taken part in the riots that accompanied the 1865 general election, when troops were called in to quell the crowds who had gathered in the Market Square for a Liberal Party rally. Nottingham’s reputation for flaring up – literally in 1831 when Nottingham Castle was set on fire – during times of political tension had been established since the 1780s and towards the end of the 19th century, political hustings were banned from the Square altogether.

The early Foresters may have had sympathy with political radicals, but an irony of these years is that as the clubs from the North-West pressured the FA to allow professionalism, thus opening up the game to players on the basis of ability rather than background, Forest aligned themselves with the (literally) old school ethos of Corinthians, the team of idealistic gentleman amateurs who would not deign to play competitive matches, let alone take a wage (though many of their players seemingly had no qualms about putting in large expenses claims, plus ça change).

Today we may blame high wages for the destruction of the ‘working class game’, but in the Victorian age it was the snobbish attitudes of public school alumni (who would often refuse to eat with their professional – and therefore lower-class – team mates on international duty) that nearly destroyed the game. While the FA saw sense and allowed professionalism, despite the protest of the traditional (mostly London-based) amateur clubs, the rugby code’s governing body clung hopelessly to its prestigious roots and lost out in the tussle to become the nation’s favourite team sport. Meanwhile, Forest, who finally started hiring professional players in 1890, lost ground to Notts County who had become a Football League founding member two years earlier.

That was the year that was

In my own potted history of the Reds, The Glory of Forest (yes, that plug was inevitable), I mockingly pondered the absurdity of the Forest shinney club ditching their sticks to take up the kicking game in 1865, comparing it to Nottingham Panthers switching to water polo.

But in the context of the time, it was not unusual for sporting clubs to lurch between different games. Several modern football clubs, such as Sheffield United and Cardiff City, started out as cricket sides, taking up football as a way of keeping fit and maintaining team spirit during the winter months. At the legendary meeting at the Clinton Arms in the autumn of 1865, it was decided Forest would play football in the summer and bandy (another stick game, played on ice) in the winter. The fact that the other football clubs were playing the game in the winter probably led to bandy being dropped two years later.

Speaking of cricket, Philip Soar rather cheekily mentions that Notts CCC were “county champions” in 1865, which isn’t technically correct. There was no official County Championship competition until 1890 (founded partly in reaction to football’s new league structure), but the title ‘Champion County’ was applied – often retrospectively – as a sort of ‘team of the year’ prize at the end of each season.

What is true is that the Theatre Royal opened its doors in September 1865 with a performance of The School for Scandal, written nearly a century earlier by Richard Brinsley Sheridan. The theatre’s neoclassical façade would later be echoed in the architecture of the Council House, opened in 1927. It was the architect Charles J. Phipps’ second theatre project (the first of dozens), having opened Bath’s own Theatre Royal in 1863. He was inducted into the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1866.

The Theatre Royal (pictured in 1895) was commissioned by a pair of lace manufacturers and was no doubt a symbol of the town’s growing status. Aside from the surge in demand for lace, quintessential in 1860s women’s fashion, a 15-year-old Jesse Boot was helping his widowed mother run their Nottingham herbal medicine shop, while the first modern bicycles had just been unveiled in Paris, which would kick off the ‘bike boom’ of the late 1860s and eventually lead to the foundation of another iconic Nottingham firm.

The Theatre Royal (pictured in 1895) was commissioned by a pair of lace manufacturers and was no doubt a symbol of the town’s growing status. Aside from the surge in demand for lace, quintessential in 1860s women’s fashion, a 15-year-old Jesse Boot was helping his widowed mother run their Nottingham herbal medicine shop, while the first modern bicycles had just been unveiled in Paris, which would kick off the ‘bike boom’ of the late 1860s and eventually lead to the foundation of another iconic Nottingham firm.

Meanwhile in London, The Salvation Army, originally The Christian Mission, was founded by William and Catherine Booth in reaction to the devastating poverty I alluded to earlier. 1865 also saw the Metropolitan Fire Brigade created in response to a number of high-profile fires, the first time British property had been protected from fire by state money.

Queen Victoria had already been on the throne 28 years and in June her grandson, the future George V, was born. Two prominent Victorian women, both known to the public as ‘Mrs’ – the novelist Elizabeth Gaskell and the cookery book author Isabella Beeton – both died, the latter at the age of just 29.

And back in Nottingham, a Tinsley Lindley was born into yet another wealthy family in the lace trade. After attending Cambridge, he played for Corinthians before returning to Nottingham where he was perhaps the first Forest player to gain contemporary renown, even more so than our great innovator Sam Widdowson. Lindley remained an amateur throughout his playing career, even though the professional era was now well under way, and had the eccentric habit of playing matches in his walking boots.

I began this piece talking about the scarcity of contemporary accounts of Forest during the club’s formative years, but in their respective memoirs about early football and the Corinthians team, the legendary club figures of ‘Pa’ Jackson and C. B. Fry both sing the praises of Tinsley Lindley’s prowess at centre-forward. While Forest’s allegiance to the ‘Corinthian values’ may have been at odds with the general trend in football by the 1880s, not to mention the inclusive ethos implied by the choice of club colours, it’s interesting that only thanks to the likes of Lindley swimming against the tide did the Forest club come to be recognised by the wider footballing world. If Forest’s history teaches us anything, it’s that this club of ours have always been admired for not quite fitting in, for not doing things the way everyone else does them.

- As well as the books mentioned at the start, much of the research for this article comes from Richard Sanders’ highly recommended history Beastly Fury: the strange birth of British football, with additional reference to A Social History of English Cricket by Derek Birley.

More Forest History

More Forest History